ALBERTO BURRI

Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art

39a Canonbury Square - London

13/1/2012 - 7/4/2012

Alberto Burri (1915-1995) is a towering figure of abstraction whose work revolutionised the artistic vocabulary of the post-war art world. Burri’s celebration of humble materials such as sacking and tar created a new aesthetic rich in expressive power during the 1950s, and was later to prove decisive for artists associated with the Arte Povera movement. Yet, despite his stature, Alberto Burri: Form and Matter at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art from 13 January to 7 April 2012 is the first major retrospective exhibition of the artist’s work to be held in the United Kingdom. It offers a comprehensive overview of Burri’s achievement through some forty powerful works spanning four decades, ranging from rare, early figurative pieces of the late 1940s to the ground-breaking abstract works for which he is best known.

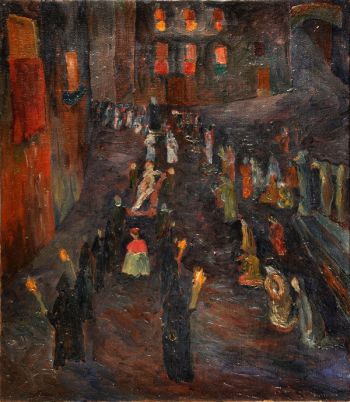

Burri was born in Città di Castello, in Italy’s central Umbria region. Originally trained in medicine, he served as a doctor in North Africa during the Second World War, but was taken prisoner in 1943 and interned in a prisoner-of-war camp in Hereford, Texas, for the remainder of the conflict. It was here that Burri first began to paint. Returning to Italy in 1946 he was awarded his first solo exhibition in 1947 at Rome’s La Margherita gallery, displaying works created in a style strongly informed by Expressionism, such as Procession of the Dead Christ (fig. 1). The current exhibition includes a number of works dating from this early period, including The Stall, Fishing at Fano and Upper Piazza (fig. 2), all dating from 1947.

The evolution of Burri’s work was rapid. Quickly abandoning his figurative style, he began to explore abstraction in vibrant yet delicate works inspired by artists such as Paul Klee (fig. 3). Between 1948 and 1950, he was to develop a revolutionary approach to image-making grounded in a poetic exploration of matter that challenged the two-dimensional nature of the wall-mounted artwork – an interest that he continued to expand and refine over the course of a long and fruitful career. Initially explored in terms of the varying textures of paint, this preoccupation swiftly led him to engage with and incorporate a wide variety of materials into his works, ranging from tar to pumice stone and, most famously, sacking (fig. 4).

These latter pieces, frequently resembling lacerated and stitched flesh, seem to contain strongly autobiographical elements relating to Burri’s medical background. Others have seen the works as a comment on Italy’s post-war economic depression, or have even related them to the coarse material of the habits worn by Franciscan monks, whose spiritual home is located at Assisi in Burri’s home region of Umbria. However, the artist himself consistently played down the significance of such associations, emphasising the works’ formal qualities rather than any anecdotal, narrative or metaphorical dimensions. In fact, Burri was reluctant to talk about his work in any context. Its meaning, he insisted, was to be found within the composition itself and nowhere else – in its tensions, its harmonies and its sense of balance or imbalance. ‘Words are no help to me when I try to speak about my painting’, he once stated, ‘they talk around the picture. What I have to express appears in the picture.’

Perhaps more than any others, these works best exemplify his ability to conjure poetry – and a powerful sense of monumentality – from the simplest and roughest of materials. In this respect, Burri’s example was to be highly influential for the work of artists such as Mario Merz and Jannis Kounellis, who likewise explored the expressive potential of ‘unglamorous’ and unconventional substances such as earth, iron and coal in their installations during the late 1960s. In terms of his own influences, Burri was able to draw on a rich Italian heritage, taking inspiration from the work of Futurist artists such as Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916). Boccioni’s 1912 Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture exhorted artists to reject the exclusivity of such ‘noble’ materials as bronze and marble, declaring that they should ‘insist that even twenty different types of materials can be used in a single work of art’. Burri was also an admirer of Enrico Prampolini (1894-1956), whose series of works from the inter-war years entitled Encounter with Matter extended the experiments of Boccioni and engaged with the notion of ‘tactilism’ first propounded by the Futurist leader, F. T. Marinetti, in the early 1920s.

Burri’s ‘sculptural’ approach to the creation of artworks reached an extreme point between 1950 and 1952 when he embarked upon his brief gobbo (‘hunchback’) series, stretching his canvases into a range of distorted shapes by means of the incorporation of wooden inserts that made it appear as if living forms, trapped within the work’s frame, were struggling to free themselves. In their rejection of the notion of an inviolable flat picture plane, these works reflected ‘spatial’ aspirations equivalent to those embodied by Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases, created around the same time. However, Burri quickly turned away from such experiments and returned to his investigation of the poetic qualities of materials, his stated aim being to discover what they were ‘capable of’, compositionally and constructively-speaking.

In 1951 Burri co-founded the Gruppo Origine along with the artists Giuseppe Capogrossi, Mario Ballocco, and Ettore Colla. It was the latter with whom Burri had the greatest affinity as Colla likewise constructed his pieces from the detritus of modern life, most famously scrap metal. From the late 1950s, Burri began to work with iron (fig. 5), and went on to experiment with other, more synthetic, industrial materials such as the insulating board cellotex from the mid 1970s (fig. 6). Around 1954 Burri also began to char, scorch and melt his materials to obtain unpredictable effects and to incorporate a greater element of chance into his compositions (figs. 7 & 8). In this context, he was to become a leading protagonist of Art Informel, a Europe-wide tendency at this time that focused on the artistic process as much as the finished product and which, in its more painterly manifestations, mirrored the aesthetics of American Action Painting through its emphasis on the importance of the artist’s gesture. Perhaps for this reason, Burri’s work achieved great success in the United States, where it was exhibited at the Guggenheim Museum and was much admired by artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly. His international popularity was demonstrated at Sotheby’s recent Italian sale in London when a 1957 work established a new auction record for the artist, selling for over £3 million.

In addition to a large number of signature pieces from the key period 1950 to 1980, the exhibition will also include several fascinating examples of works created in a range of media and techniques perhaps less commonly associated with the artist, including a series of rare and elegant prints. Curated by the art historian Massimo Duranti, it represents a long overdue reconsideration of one of the undisputed masters of the 20th century. The exhibition has been organised under the patronage of Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini in Città di Castello – the largest repository of Burri’s works, bequeathed by the artist to his hometown – and draws on a number of important public and private collections in Italy and the United Kingdom, including Tate Modern, the Musei Vaticani and the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome.